Courts Keep Shredding Online Contract Formation Processes–McGhee v. NAB; Applebaum v. Lyft

A couple more online contract formation cases to enliven your Saturday:

McGhee v. NAB

This case involves mobile credit card processing services. The plaintiffs are merchants who think they were overcharged for card readers. The vendor invoked the arbitration clause in its terms. The vendor alleges that “when McGhee signed up for NAB’s credit card processing services, McGhee was required to accept the ‘Terms and Conditions’ by clicking on a button next to the words ‘I have read and agree to the Terms and Conditions.'” Sounds like an easy case, right?

First, the court calls this implementation a “modified clickwrap” and says a “modified clickwrap agreement is similar to a browsewrap in that the user is not required to scroll through a list of terms and conditions before reaching the “I Agree” button, but the user is otherwise ‘required to affirmatively acknowledge the agreement before proceeding with use of the website.'” Why is it a “modified” click”wrap” and not just a clickwrap? (Better yet, let’s chuck all the BS “wrap” nomenclature and just call it a “clickthrough agreement”). It doesn’t make sense to distinguish between a “modified clickwrap” and a “clickwrap” unless courts thinks the results might differ based on this characterization, which would be really stupid. This reinforces the point we’ve expressed a few times that contract formation calls-to-action should require an extra click, like “By checking this box, I agree to the T&Cs” with a separate checkbox from the account creation button. If courts are going to do stupid things like distinguish between “modified clickwraps” and “clickwraps,” go ahead and take away any grounds for courts to make that stupid distinction.

Second, the vendor’s contract was articulated in at least two documents, the “terms and conditions” and a separate “user agreement.” The account formation page (and associated call to action) linked to the terms, which then further linked to the user agreement that contained the desired arbitration clause. This two-step process isn’t inherently defective (the court says “Even this two-step process could conceivably fall within the parameters of a modified clickwrap agreement”), but it can lead to trouble. Here, the vendor muffs it because the terms contained its own forum selection clause specifying litigation in Georgia courts, while the user agreement contained a conflicting mandatory arbitration clause. Oops. Plus, the terms had a merger clause integrating all other agreements, so the court has no problem giving priority to the directly linked terms instead of the merged-out user agreement two links away.

The vendor tries some fancy footwork to get out of this jam, saying that the terms don’t apply because the merchants never filled out the requisite account application. The court turns this argument around, asking why the terms were referenced in the contract formation call-to-action if the vendor was going to argue they didn’t apply. With a hint of deadpan, the court says “If NAB intended to have the “Pay Anywhere User Agreement” control McGhee’s claims, perhaps NAB should have linked the application to that agreement.”

The vendor did not intrinsically do something wrong by having two documents with terms and linking one into the other. This happens all of the time. However, if an online vendor has multiple separate documents all purporting to be part of the termset governing users, extra care has to be taken to ensure all of the documents work together seamlessly. When those separate documents have separate owners, the risk of a collision between the documents goes up substantially. Those documents need a permanent single owner, or perhaps the separation of documents entails more risk than it’s worth.

While the merchants won this round, the court has a parting gift for the vendor. In a footnote, the court notes: “While McGhee may have won the day, the Court notes that the Terms and Conditions McGhee himself points to as controlling include a forum selection clause and class action waiver.” Be careful what you wish for!

Case citation: McGhee v. North American Bancard, 2017 WL 3118799 (S.D. Cal. July 21, 2017)

Applebaum v. Lyft:

The Uber and Lyft contract formation rulings are coming out faster than we can blog ’em, so we have not attempted to blog them comprehensively or even representatively. Still, this one caught my eye, so I’m blogging it even if it may overlap with multitudinous other rulings we haven’t been able to digest.

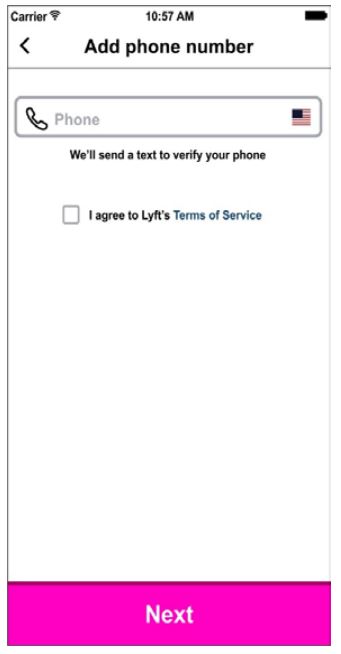

The case involves passengers suing for allegedly being overcharged for tolls. To install the Lyft app, at the time the named plaintiff registered, passengers saw this screen:

“The plaintiff could not click the pink “Next” bar (which was necessary to create a registered profile) until he entered his phone number into the “Phone” field and clicked the box (the “Box”) adjacent to the phrase ‘I agree to Lyft’s Terms of Services.'”

During the litigation, Lyft modified its terms of service, including its arbitration clause. Apparently Lyft implemented the new terms by requiring clickthroughs from all members:

The screen contained the entire September 30, 2016 Terms of Service and was scrollable. An existing Lyft customer could not book a ride after September 30, 2016 unless the customer clicked the pink “I accept” bar.

The court says the initial contract formation process failed even though it was a “clickwrap”:

a reasonably prudent consumer would not have been on inquiry notice of the terms of the February 8, 2016 Terms of Service. Lyft’s registration process, as it existed when the plaintiff accessed it in April 2016, did not alert reasonable consumers to the gravity of the “clicks,” namely, that clicking the Box and then the pink “Next” bar at the bottom of the screen constituted acceptance of a contract, including an arbitration agreement, governing the parties’ obligations going forward. Instead, the design and content of the registration process — especially compared to the respective processes that existed for the July 28, 2014 Terms of Services and the September 30, 2016 Terms of Service (the latter of which is discussed below) — discouraged recognition of the existence of lengthier contractual terms that should be reviewed.

Initially, the text is difficult to read: “I agree to Lyft’s Terms of Service” is in the smallest font on the screen, dwarfed by the jumbo-sized pink “Next” bar at the bottom of the screen and the bold header “Add Phone Number” at the top. The “Terms of Service” are colored in light blue superimposed on a bright white background, making those “Terms of Service” — which Lyft argues are the operative words that would alert a reasonable consumer to inquire about a contract — even more difficult to read.

A reasonable consumer would not have understood that the light blue “Terms of Service” hyperlinked to a contract for review. Lyft argues that coloring words signals “hyperlink” to the reasonable consumer, but the tech company assumes too much. Coloring can be for aesthetic purposes. Courts have required more than mere coloring to indicate the existence of a hyperlink to a contract…. Beyond the coloring, there were no familiar indicia to inform consumers that there was in fact a hyperlink that should be clicked and that a contract should be reviewed, such as words to that effect, underlining, bolding, capitalization, italicization, or large font.

Seriously, did the court just say that online users don’t know that light blue text on a screen is probably a hyperlink? I’d love to put that question to a focus group or a survey. We’ve had 20 years of experience with 10 blue links from Google search results! Anyway, the court continues:

Rather than providing notice to consumers that they were agreeing to the terms of a contract, the screen with the Box to be checked for “Lyft’s Terms of Service” was misleading. The screen was titled in bold terms “Add Phone Number.” The entire screen was structured as part of a process to verify a phone number, not to enter a detailed contractual agreement. A reasonable consumer would have thought that the consumer had agreed to be contacted by Lyft, specifically, to receive a text message from the company. A consumer would have arrived at this screen after entering personal information on several similar screens; there was nothing to denote that this screen was special or distinguishable from the rest. The “Add phone number” screen called upon the consumer to input the consumer’s telephone number, with the proviso: “We’ll send a text [message] to verify your phone.” Only then would the consumer click the Box next to “I agree to Lyft’s Terms of Services,” which was immediately below Lyft’s statement that it was going to contact the consumer. The reasonable inference for the reasonable consumer was that the Terms of Service related only to the text verification because the consumer had just agreed to receive a text message. This conclusion would have been reinforced by the design of the screen, including the inconspicuousness of the hyperlink and the absence of cautionary language to indicate that there were contractual terms for review, let alone important contract terms. A reasonable consumer may have understood that the consumer had agreed to something, but not to the lengthy February 8, 2016 Terms of Service.

I’m sure most of you have spit your coffee on the screen by now. “A reasonable consumer may have understood that the consumer had agreed to something, but not to the lengthy February 8, 2016 Terms of Service.” WTF? The court then discounts the significance of the mandatory “next” bar:

a consumer could not click “Next” until the consumer had entered his or her phone information for text verification. As Lyft conceded at oral argument, this was true for every screen in the registration process: each screen contained a “Next” bar (or similar prompt), and a consumer could not proceed to the next screen until completing the required fields on each screen. Thus, this limitation would not have alerted a consumer to the significance of the Box, especially given that the word “Next” implied that there were additional steps in the registration process.

The court also says consumers don’t understand what the words “terms of service” mean in the abstract.

Yet, Lyft saves the day. The September 30, 2016 amendments were presented as a “scrollwrap” (UGH), so…

The method for presenting the September 30, 2016 Terms of Service to existing customers who had already registered conspicuously cured the defects in the notice for the February 8, 2016 Terms of Service. Rather than a screen headed “Add Phone Number,” the September 30, 2016 Terms of Service were presented on a screen titled “Terms of Service,” where, given the content and design of the screen, there could be no doubt as to what that phrase signified. The screen explicitly stated: “Before you can proceed you must read & accept the latest Terms of Service.” The Terms of Service were set out on the screen to be scrolled through. No subtle hyperlink was needed. The Terms of Service begin with the warning: “These Terms of Service constitute a legally binding agreement … between you and Lyft, Inc.” Before proceeding, the user was required to click on a conspicuous bar that said: “I accept.”

So Lyft gets its arbitration despite the failed initial clickwrap, and current and future users will get more prolix contract formation implementations. Yay…?

I’m pretty sure that 5 years ago, 95%+ of us would have said that the Lyft screenshot depicted above was an airtight contract formation. After all, it required an extra click! Yet, the formation bar has moved substantially in the past few years. When the engineers and product teams keep pushing for “lightweight” contract formation processes because everyone else is doing “lightweight” implementations, show them how Lyft barely dodged the bullet in this case.

Case citation: Applebaum v. Lyft, Inc., 2017 WL 2774153 (SDNY June 26, 2017)