How a Chipmunk Emoji Cost an Israeli Texter $2,200

by Gabriella Ziccarelli and Eric Goldman

[Eric’s introduction: Gabriella is a star SCU Law alum and an associate at Blank Rome in DC. She is also a former Internet Law student of mine. As a teacher, it’s gratifying to have a former student on my blog to share the expertise they’ve accumulated since my course. Gabriella had been writing and speaking on emoji legal issues before I even began my paper on Emojis and the Law. She has graciously agreed to help us understand a recent Israeli court ruling interpreting emojis in a contract setting.]

We have not seen many judicial opinions carefully parsing the meaning of emojis (or even discussing the methodological tools for parsing their meaning), but we expect we’ll regularly see such cases soon enough. As part of the emerging caselaw, last month an Israeli court issued an interesting opinion about the meaning of emojis that’s worth a closer look.

A landlord and prospective tenant were communicating about an available apartment. The prospective tenant’s text messages expressed enthusiasm for renting the apartment and included numerous emojis. In reliance on the positive messages, the landlord believed the tenant would rent the apartment and took it off the market. The parties started negotiating the lease, but the tenant eventually ghosted the landlord. As a result, the landlord put the apartment back on the market and found another tenant.

Israeli Judge Amir Weizebbluth of the Herzliya Small Claims Court awarded the landlord $2,200 in damages, explaining:

This is the place to refer once again to those graphic symbols (icons) sent by Defendant 2 to the Plaintiff. As stated, they do not, under the circumstances, indicate that the negotiations between the parties have matured into a binding agreement. However, the sent symbols support the conclusion that the defendants acted in bad faith. Indeed, this negotiation’s parties’ ways of expression may take on different forms, and today, in modern times, the use of the “emoji” icons may also have a meaning that indicates the good faith of the side to the negotiations. The [emoji laden] text message sent by Defendant 2 on June 5, 2016, was accompanied by quite a few symbols, as mentioned. These included a “smiley”, a bottle of champagne, dancing figures and more. These icons convey great optimism. Although this message did not constitute a binding contract between the parties, this message naturally led to the Plaintiff’s great reliance on the defendants’ desire to rent his apartment. As a result, the Plaintiff removed his online ad about renting his apartment. Even towards the end of the negotiations, in the same text messages sent at the end of July, Defendant 2 used “smiley” symbols. These symbols, which convey to the other side that everything is in order, were misleading, since at that time the defendants already had great doubts as to their desire to rent the apartment. The combination of these – the festive icons at the beginning of the negotiations, which created much reliance with the prosecutor, and those smileys at the end of the negotiations, which misled the Plaintiff to think the defendants were still interested in his apartment – support the conclusion that the defendants acted in bad faith in the negotiations. Even if I assume that the reason for the withdrawal from the negotiations was justified, the defendants should have notified the Plaintiff on 8 July, 2016 that they are not sure of their desire to rent the apartment, and that the Plaintiff should consider his steps accordingly. The defendants “dragged” the Plaintiff, “lulled” him, until he found himself close to the beginning of the lease period without having found a renter.

[Note: this translation came from the site Room404. We haven’t validated the translation.]

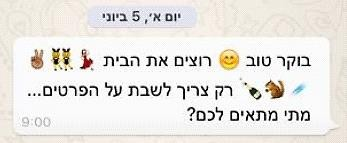

Here is the prospective tenant’s initial message:

According to Room404, this translates into:

Good morning ? Interested in the house ???✌️☄️?️?️ Just need to discuss the details… When’s a good time for you?

The court also discusses a later text message containing a smiley. As the parties were negotiating the lease, the prospective tenant explained a delayed response by saying (also a Room404 translation): “It’s just that we’re moving the entire house to storage on Tuesday so we’re a little busy.. No worries! I will update Nir :)” [Nir was the prospective tenant’s co-tenant] The court says the final two characters, the noseless smiley emoticon, expressed positive intent.

We’re not familiar with Israeli law on contract formation or “bad faith negotiations.” Under US law, there are no legal consequences for “bad faith” communications during failed contract negotiations except in special circumstances. Generally, the law is caveat emptor/vendor. As a result, US law most likely would have expected the landlord to keep running ads for the apartment, and accepting backup lease offers, until a lease was signed. Perhaps the court’s ruling turns on something specific to Israeli law.

US law would probably agree with the court’s conclusion that no contract formed. The initial text message contains obvious equivocation. First, it says the prospective tenant is “interested” in the house. Ordinarily, we’d treat interest in a transaction differently than a commitment to the transaction. Second, the initial message makes clear that the prospective tenant still wants to discuss details. The details are unspecified and could be major deal points. Because of this equivocation, ordinarily we would not treat this message as a manifestation of assent sufficient to constitute an offer or an acceptance. Similarly, the text’s equivocation ordinarily would not support a promissory estoppel claim because the landlord’s detrimental reliance on pre-lease negotiations isn’t reasonable. The subsequent text message is just ordinary negotiation chatter.

However, in interpreting the messages, we can’t just consider the text and ignore the emojis (or emoticon). Because we must assume the prospective tenant included them for a reason, how do the emojis modify or supplement the initial text message’s words?

In the initial text message, the smiley follows the words “good morning.” The smiley doesn’t seem to signal any contractual intent; it’s likely just a friendly flourish to the “good morning” introduction. See Marcel Danesi, The Semiotics of Emoji (2017), explaining that emojis are frequently used as emotional supplements to preceding words or sometimes even used as a punctuation substitute. Therefore, it’s probably incorrect for the judge to interpret the smiley as evidence of the prospective tenant’s optimism about the transaction.

The smiley emoticon in the subsequent text message has many possible meanings. It could have meant that the deal was still on. Alternatively, it could have been included to blunt what the landlord might have interpreted as bad news (the prospective tenant’s continued delays). It could have also been used to admit embarrassment over the delay. It could even be facetious. If the prospective tenant had used the “thumbs up,” “ok” or “check mark” emojis instead of the smiley emoticon, would those have been clearer about the prospective tenant’s intent to accept the lease?

There are 6 more emojis in the initial text message following the words “interested in the house” (again, as Danesi posited, these emojis likely modify or supplement the preceding words):

- a ballerina

- women with bunny ears (also known as the dancing girls emoji)

- the victory hand (also known as the peace sign emoji)

- a comet

- a chipmunk

- a champagne bottle

What do these emojis mean in this context? We’re not sure. First, emojis develop geographically regional meanings, so it’s possible or probable that Israelis assign different meanings to these emojis than we assign to them in the United States. Second, even within the same geography, different subcommunities assign different meanings to individual emojis. The women with bunny ears emoji, for example, has several meanings. According to Emojipedia, the “two-person version of this emoji is often used as a display of friendship, fun, or ‘let’s party.'” Given that the prospective tenants were a couple, perhaps this emoji symbolized their excitement. (There is a separate emoji for a single woman with bunny ears, which is why it may be significant the prospective tenant chose the couples’ version). Finally, the interpretation of emojis is individually subjective. As Gabriella discusses in her Inside Counsel article, emojis are more likely to have individually subjective meanings than text-based communications because emojis are “not restricted to the confines of definitions, but rather expanded by the sender and receiver’s perceptions, experiences, and context.”

Furthermore, if we’re trying to parse the emojis meaning, we also have to consider the meaning of all the emojis–including the chipmunk and comet emojis, and those emojis do not have any clear meaning in this context. Also, we lack consistent grammar rules for emoji sequences, so did the prospective tenant mean for each subsequent emoji to modify the preceding emojis, and if so, how does that affect their meaning? In other words, does the fact that the chipmunk followed the comet affect their respective meanings?

The court is also wrong to assume, without any further evidence, that the six emojis signaled positive intent. As Eric discusses in his paper, individual emojis routinely are viewed by some folks as positive and other folks as negative, sometimes in unpredictable ways. For example, the “bento box emoji is used in largely negative contexts, while the panda face is associated with less positive emotions than most other animals featured on the emoji keyboard.” So the court treats the chipmunk and comet emojis as positive expressions, perhaps because they are surrounded by other emojis that might have positive connotations, but we don’t know what percentage of folks would actually assign negative valences to those symbols.

Finally, the court does not consider whether the landlord and tenant saw the same emojis on their screens. This is not guaranteed due to the fact that platforms implement Unicode emojis idiosyncratically. It’s unclear if that is an issue here, but it might be. For example, there is substantial variation in how platforms implement the women with bunny ears emoji, and the differences (even if subtle) could affect the emoji’s meaning to the landlord and tenant.

Overall, it seems like the court’s opinion overanalyzes the emojis. This case involves the very common situation where a vendor must decide whether to take its merchandise off the market while negotiating with a hot prospect or keep shopping the merchandise around to other potential buyers. To keep the vendor from pursuing other buyers, the hot prospect sent numerous messages designed to demonstrate continued interest. It’s the repeated expressions of interest that seemed to dictate the outcomes, not the emojis per se. In other words, the court probably would have reached the bad faith conclusion even if the text messages contained no emojis or emoticons, because the prospective tenant’s messages (both in substance and frequency) were positive enough (without the emojis) to string the landlord along.

Naturally, it’s unreasonable to expect this judge to be an emoji expert. This was a small claims court, where justice is often driven by equity more than formalist legal rules; and the low dollar stakes meant that neither the judge nor the litigants were going to invest in experts to explain the nuances of emojis. So even if this opinion wrongly interpreted the emojis, it’s not necessarily predictive of what we’ll see in future cases that are more vigorously litigated. Still, the ruling is a good reminder that we anticipate courts are going to see lots of emoji issues, and they may not be fully prepared for that onslaught.

[UPDATE: Amit Elazari, a Berkeley Law doctoral student and an expert in Israeli contract law, emailed me: “Israeli law in general and contract law, in particular, embraces good faith is an underlining tenet, a fundamental principle which informs courts in their decisions and purposeful interpretation of the law. Israeli contract law explicitly confers upon the parties (and their representatives) an extensive duty to negotiate in good faith [Contracts (General Part) Law, 5733-1973, 27 LSI 117 (1972-1973) at § 12], regardless of whether a contract was formed. A breach of such duty may give rise to damages, and in special circumstances, specific performance remedy or expectation damages. In this case, the court awarded the landlord reliance damages (amounting to one month rent) because it found the prospective tenets breached their duty by neglecting to inform the landlord they are still debating whether to take the apartment, while sending the landlord “reassuring text messages” (such as “don’t worry!”) thereby deluding the landlord to believe everything is in order. The court referred to the emojis in this analysis, noting that “the emojis support the conclusion the defendants acted in bad faith”]

Some other coverage of this case:

Room404: ???✌️☄️?️? Show Intention to Rent Apartment, Says Judge

Quartz: ???✌️☄️?️? Emojis prove intent, a judge in Israel ruled

Thrillist: This Couple Lost Thousands in a Lawsuit Over a Stupid Emoji

Case citation: Dahan v. Shacharoff, 30823-08-16 (Herzliya Small Claims Court Feb. 24, 2017)