Comments on the Internet Association’s Empirical Study of Section 230 Cases

Elizabeth Banker of the Internet Association has posted “A Review Of Section 230’S Meaning & Application Based On More Than 500 Cases.” This complements Prof. David Ardia’s comprehensive empirical study of Section 230 caselaw from a decade ago. It’s great to have a fresh look at the cases. (I’ll discuss the methodology limitations in a bit).

Elizabeth Banker of the Internet Association has posted “A Review Of Section 230’S Meaning & Application Based On More Than 500 Cases.” This complements Prof. David Ardia’s comprehensive empirical study of Section 230 caselaw from a decade ago. It’s great to have a fresh look at the cases. (I’ll discuss the methodology limitations in a bit).

The report’s summary (bolded for emphasis):

The importance of Section 230 is best demonstrated by the lesser-known cases that escape the headlines. These decisions show the law continues to perform as Congress intended, quietly protecting soccer parents from defamation claims, discussion boards for nurses and police from nuisance suits, and local newspapers from liability for comment trolls.

* * *

Let’s look more closely at the report’s six major findings:

“Finding #1: A wide cross-section of individuals and entities rely on Section 230.”

My comment: Google and Facebook qualify for Section 230, but anyone serious about Section 230 reform should pay close attention to the other services that rely on Section 230. The report identifies numerous beneficiaries: “Online users; internet service providers and website hosts; newspapers; universities; libraries; search engines; employers; bloggers, website moderators and listserv owners; social media companies; marketplaces; app stores; spam protection and anti-fraud tools; and domain name registrars.” Section 230 reform will almost certainly hurt the less-heralded beneficiaries of Section 230–and the pro-speech outcomes they promote–while entrenching the incumbents.

“Finding #2: Section 230 immunity was the primary basis for decision by a court in only 42 percent of decisions reviewed. Courts required factual development of cases where there was a question as to whether the platform played a role in the creation or development of the content at issue.”

My comment: Judges have multiple ways of resolving a case and a lot of discretion choosing between these options. Sometimes they choose procedural technicalities to avoid talking about substance at all. Sometimes they opine on every issue litigated by the parties. Other times they choose to address one dispositive issue and sidestepped the others. I routinely see clearly doomed cases were the court rejected or didn’t opine on Section 230 only to dismiss the case on other grounds. (Here’s a fine example). For that reason, Section 230 can be helpful to judges because the statute provides a fast lane to reach what may be the obvious outcome, rather than necessitating a time-consuming and expensive process that is clearly going to reach the same outcome.

“Finding #3: A significant number of claims in the decisions failed without application of Section 230 because courts determined that they lacked merit, or dismissed them for other reasons.”

My comment: There is no benefit to amending Section 230 if other law dictate the same substantive outcome. In those cases, the reform screwed up Section 230 for no countervailing benefit; and the reform made everyone worse off by increasing the adjudication costs.

“Finding #4: Forty three percent of decisions’ core claims related to allegations of defamation, just like in the Stratton Oakmont v. Prodigy Services case that spurred the passage of Section 230.”

My comment: This percentage seemed high. I wonder if older cases skewed this up. I also wonder if this might be an artifact of the case indexing methodology.

“Finding #5: Cases involving allegations of federal or state criminal activity were frequently decided in whole, or in part, on other grounds.”

My comment: This area definitely would benefit from further study.

“Finding #6: Section 230 protects providers who engage in content moderation, but typically through application of subsection (c)(1) rather than (c)(2).”

My comment: with courts interpreting Section 230(c)(1) to cover content and account removals, the use cases for Section 230(c)(2) have narrowed. However, Section 230(c)(2)(B) still plays an essential role for anti-threat software makers, at least until jeopardized by the Enigma v. Malwarebytes ruling.

* * *

Comments About the Paper’s Methodology

In a footnote, the report says “this summary and IA’s review do not purport to be a comprehensive review and — given the complexities of trying to draw generalizations from litigation — is far from perfect. Our demonstrates that a fuller review from an institution better equipped to perform such a study would offer significant value to the conversation.”

Amen. However, I’m not volunteering to do that fuller review. Empirical caselaw projects are hard. So I hope someone else follows up as suggested. I’d love to see the work.

The IA dataset includes 516 cases. The methodology explained that the dataset was initially built with a snowball methodology, followed by searches in free legal search engines (but apparently not Lexis/Westlaw).

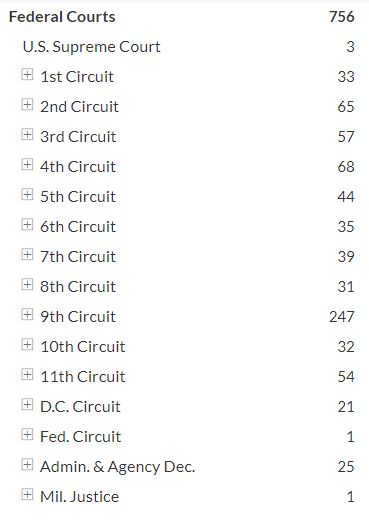

On July 27, I checked with Shepard’s on Lexis and it lists 977 citing references for 47 USC 230–756 federal decisions and 219 state court decisions. Here is the breakdown in federal court by courts in each circuit:

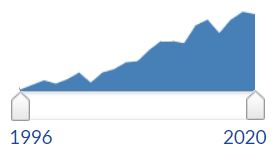

The tool charts the relatively linear growth of citations over time:

The 977 Shepard’s cites aren’t directly comparable to the 516 cases in the IA dataset. The IA dataset apparently only indexed a case once, even if it produced multiple rulings; while Shepard’s counts multiple rulings in the same case.

On the other hand, Shepard’s 977 tally is still incomplete. Westlaw’s citation count is 824, and I would expect Westlaw contains 100-200 citations that Lexis does not. Furthermore, I routinely post opinions that neither index include. So I think the total universe of Section 230 case citations is more like 1,200+. If so, the IA dataset probably contained less than half of the indexable cases.