Browsewrap/Clickwrap Distinction Vexes Another Court–Nevarez v. Ticketmaster

We just blogged about online contract formation yesterday, but it’s worth revisiting the topic so quickly because this case demonstrates another crash-and-burn failure of the browsewrap-clickwrap dichotomy. How many times must the “wrap” categorization fail before judges recognize that it’s a complete waste of time?

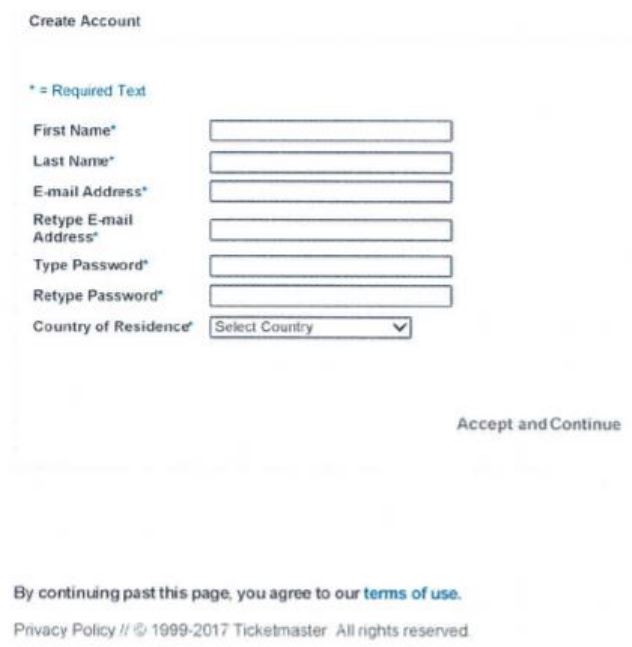

The plaintiff alleges that Ticketmaster violates the ADA for admission ticket and parking sales for Levi’s Stadium. Ticketmaster seeks to send the case to arbitration. To buy tickets, purchasers needed a Ticketmaster account, which included the following screen (helpfully included in the opinion):

While this might have been close to state-of-the-art when it was launched (this case involves purchases from 2015), this screen is clearly suboptimal based on more recent cases. The call-to-action is effectively in the footer, and it isn’t as close to the “accept and continue” button as it should be, creating the possibility that some users won’t see the call-to-action. At minimum, the call-to-action should be above the button, not well below it. The call-to-action language (“by continuing past this page”) is unambiguous, but it could and should expressly reference the action users will actually take on the page. And, of course, without a bonus click to assent specifically to the TOU before clicking to the next screen, courts are now saying this isn’t a clickthrough agreement, which puts its formation in limbo.

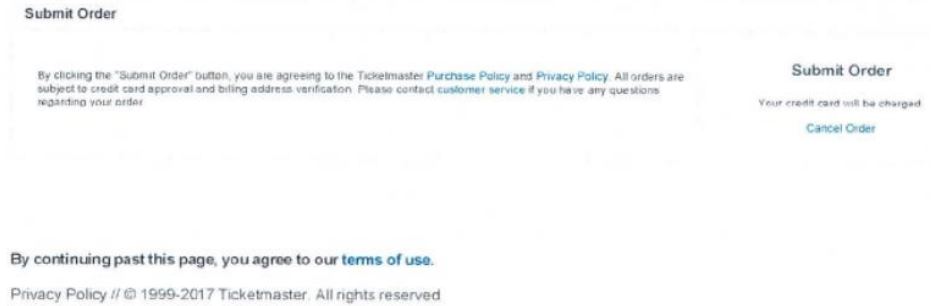

Ticketmaster’s purchase page also references legalese:

This looks pretty good for formation of the purchase policy and privacy policy…but the arbitration clause isn’t contained in those. The purchase policy integrates and links to the TOU.

Required to apply the the dreadful Nguyen Ninth Circuit opinion, the esteemed Judge Koh says that Ticketmaster’s implementation isn’t a browsewrap or a clickwrap. Surprise! Well, actually not the least bit surprising, because most cases nowadays are finding that the litigated formation process isn’t either a browsewrap or a clickwrap, or worse, saying that it’s some of both. It’s a strong clue that the browsewrap-clickwrap definitions are terrible when they fail more often than they work.

Stuck with useless and distracting definitions, Judge Koh does what most judges are doing: she recites and analyzes the browsewrap/clickwrap characterization only to discard all of that discussion when it proves useless. Judge Koh says:

In any event, regardless of whether the Ticketmaster Website’s TOU are most appropriately labeled as a “browsewrap” or a “clickwrap” agreement, the Court finds that Plaintiffs assented to the Ticketmaster Website’s TOU in purchasing their tickets and parking passes on the Ticketmaster Website. Indeed, courts have “consistently enforced” arbitration clauses contained within terms of use on similarly designed websites…

the Ticketmaster Website prominently informed Plaintiffs on at least two occasions prior to purchasing their ticket or parking pass that, by clicking either “Accept and Continue” or “Sign In” to register or sign in to their account, and by clicking “Submit Order” to finalize their purchase, Plaintiffs were agreeing to the Ticketmaster Website’s Terms of Use, “which were always hyperlinked and available for review.” In addition, Plaintiffs were explicitly told that by clicking “Submit Order” they were agreeing to the Ticketmaster Website’s Purchase Policy, which further informed Plaintiffs in the first paragraph that their use of the Ticketmaster Website was governed by the Ticketmaster Website’s TOU.

So exactly what did Ticketmaster do right? The opinion doesn’t say definitively, but the repetitive exposures to TOU links didn’t hurt because the judge obviously believed that buyers knew they were bound to terms. Still, as we discussed yesterday, modern state-of-the-art requires a two-click formation process to avoid living on the edge like Ticketmaster did.

The court also rejects an unconscionability challenge. Adhesion contracts have some procedural unconscionability, though that was blunted by the fact that the plaintiff could purchase tickets at the stadium box office rather than online (and actually did so). Ticketmaster’s designation of JAMS as the arbitration service provider helped with the substantive unconscionability analysis. The plaintiff alleged the arbitration service fees were too high compared to his meager income, but JAMS waives arbitration fees for the indigent. Further, JAMS only charges plaintiffs a $250 fee, which is about the same as court filing costs. Ticketmaster agreed to pick up all other costs (except attorneys fees). This was good enough to satisfy Judge Koh. It’s a reminder that you need to really scrutinize your arbitration clause (in conjunction with the arbitration service provider rules you’re opting into) to ensure that it doesn’t have any gotcha consequences to plaintiffs that will spur judicial skepticism–even if that means you may have to occasionally pay out some unmerited arbitration fees. Consider those an investment in good arbitration clause hygiene.

Case citation: Nevarez v. Forty Niners Football Company, LLC, 2017 WL 3492110 (N.D. Cal. Aug. 15, 2017)