Faulty Mobile Device User Interface Jeopardizes Uber’s Contract Formation–Metter v. Uber

This is a lawsuit against Uber alleging that it improperly assessed a cancellation fee without advising the rider in advance. Uber sought to compel arbitration. The court declines.

This is a lawsuit against Uber alleging that it improperly assessed a cancellation fee without advising the rider in advance. Uber sought to compel arbitration. The court declines.

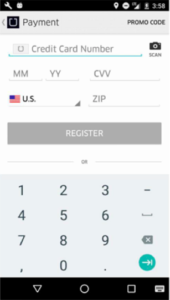

The arbitration clause is contained in Uber’s terms of service, and the court considers whether the rider agreed to the terms. The court focused on the registration process. The court notes that, during the sign-up process, an alert states “BY CREATING AN UBER ACCOUNT, YOU AGREE TO THE TERMS OF SERVICE & PRIVACY POLICY.” The terms of service were actually linked from the “TERMS OF SERVICE” text. When the plaintiff entered his credit card information, however, a numerical keypad popped up and this keypad “obstructed the previously visible terms of service alert”.

The court says enforceability of the terms depends on whether the user had “reasonable notice” of the terms of service (citing Nguyen). Reasonable notice means either actual or constructive notice, and constructive notice is where the consumer is on inquiry notice and “takes an affirmative action to demonstrate assent to them.”

Plaintiff raised several arguments as to why he did not assent: (1) the alert is not sufficiently conspicuous; (2) the alert is confusing and does not call out the waiver of the right to jury trial; (3) the alert is a “browsewrap” agreement; and (4) the pop-up blocked his view of the terms of service.

The court dismisses the first three arguments, specifically noting that Uber’s terms are not a browsewrap and there is no special requirement to call out arbitration in this sort of an assent. However, as to the keypad blocking his view of the terms, the court agrees. Uber argued that he would have viewed this alert before he went to enter his credit card information, but the court says there is nothing in the process that would lead to the conclusion that he would have necessarily looked at the terms before. There was no instruction telling him to scroll down, and of course the payment screen is the screen where consumers would expect to see the operative terms. This is fatal:

As a result, an ordinary registrant will often be compelled to activate the pop-up keyboard and obscure the terms of service alert before having the time or wherewithal to identify other features of the screen, including the alert. When such a registrant presses “REGISTER” without having seen the alert, he does so without inquiry notice of Uber’s terms of service and without understanding that registering is a manifestation of assent to those terms. Although the terms of service alert seems designed to put a registrant on inquiry notice of Uber’s terms of service and to alert the registrant that registration will amount to affirmative assent to those terms, the keypad obstruction is a fatal defect to the alert’s functioning.

This is not to say that a litigant can merely defeat a motion to compel by claiming he or she never saw the alert. Here, he made a plausible argument to this effect, and the apps functionality appears to conform to his allegation.

Uber argued he was judicially estopped from disclaiming the agreement because he relies on it in his complaint. But the court says the fact that he relied on some agreement with Uber does not mean he necessarily concedes the enforceability of the terms.

__

We’ve blogged a lot about online terms lately, but there have been relatively few cases examining how agreement to terms of service plays out differently on a phone than on a computer. This is a great example of how an online interface (in this case the court focuses on a particular implementation) makes all the difference.

I imagine a spirited argument between members of the legal and UX/UI teams regarding whether to simply make the customer check the box. It does not take a legal genius to see how that would put you in a better position, and the fact that companies often decline to take this step makes me think the conversion cost must be steep.

Other things Uber could have done here? Implement a screen that the user must see but perhaps take no action in response to? Send an email alert after the fact?

Courts make assumptions regarding customer behavior in this context. A court could have just as easily said that no reasonable consumer would give their credit card to an app without some sort of terms of service and the fact that the terms were not so prominently presented is not dispositive. But typically companies do not get the benefit of the doubt in this context.

Eric’s Comments: Unless I missing something, it seems like most Uber passengers would have been exposed to a similar user interface. Thus, if Uber loses this case, its contract may be invalidated for many or all Uber passengers. If so, this is an incredibly high-stakes case for Uber.

In terms of prospective guidance, Venkat’s suggestion is a good one: though not necessarily legally required, at this point every online contract should require a mandatory check-the-box to proceed. Notice how a mandatory checkbox would have mooted all potential problems caused by popups. As a vastly inferior second-best option, contract formation screens need to be popup-free zones. I know sometimes sites display the terms in a popup screen over the registration page, but this case shows the risk that things might go unexpectedly wrong with the popups in a way that jeopardizes the primary goal.

Case Citation: Metter v. Uber Techs., Inc., 2017 U.S. Dist LEXIS 58481 (N.D. Cal. Apr. 17, 2017)

_____

HIDDEN TRACKS #1 By Eric: More Uber Contract Formation Cases

The Uber cases are coming out more rapidly than we can blog them. Some other cases I’ve flagged in 2017:

Cubria v. Uber Technologies, Inc., 2017 WL 1034731 (W.D. Tex. Mar. 16, 2017). This is a TCPA case against Uber. As usual, Uber invoked its arbitration clause. The plaintiff makes many of the same arguments that Metter did, but did not appear to raise the popup UX problem. The court says: “The process through which Plaintiff established her account with Uber put her on reasonable notice that the act of signing up for Uber’s services bound her to the 2013 TACs. The placement of the phrase “By creating an Uber account, you agree to the Terms of Service & Privacy Policy” on the final screen of the account registration process was prominent enough to put a reasonable user on notice of the terms of the Agreement.” The court adds that it’s less sympathetic to contract formation problems raised by power users: “Plaintiff’s argument she did not have reasonable notice of or manifest assent to the 2013 TACs is unpersuasive, especially because Plaintiff accessed Uber’s services over 300 times after clicking “DONE.” She therefore retained the benefit offered by the contract not once but 300 times, implying she consented.” As a result, Uber successfully directs the case to arbitration. Because the underlying facts appear to be identical, this case could reach a different result post-Metter.

A funny footnote: “Uber argues Plaintiff is not an unsophisticated consumer because she graduated from law school. The Court need not decide this issue and assumes, for the sake of argument, Plaintiff is an unsophisticated consumer.” Sadly, graduating from law school and being an unsophisticated consumer are not mutually exclusive…

Peng v. Uber Technologies, Inc., 2017 WL 722007 (EDNY Feb. 23, 2017). Unlike the Metter and Cubria cases, this lawsuit involves drivers instead of passengers. Uber’s contract formation with drivers appears to be different. Most obviously, “Uber drivers had to click on a “YES, I AGREE” box twice to indicate assent to Uber’s Services Agreement.” Uber amplified the user flow:

Before going online, drivers were directed to a page titled, “TERMS AND CONDITIONS”, which said on the top “TO GO ONLINE, YOU MUST REVIEW ALL THE DOCUMENTS BELOW AND AGREE TO THE CONTRACTS BELOW.”…On the bottom of the page, there was a clickable blue box with the large, capitalized words, “YES, I AGREE”. Directly above the blue box, there was a provision that read, “By clicking below, you represent that you have reviewed all the documents above and that you agree to all the contracts above.” Clicking on the “YES, I AGREE” button would cause the background of the page to go dark, and a centrally located white box would pop up, stating in bold, capitalized text, “PLEASE CONFIRM THAT YOU HAVE REVIEWED ALL THE DOCUMENTS AND AGREE TO ALL THE NEW CONTRACTS.” Drivers could click either “NO” or “YES, I AGREE”. After drivers accepted the Services Agreement, a copy automatically would be transmitted to their Driver Portal, where they could review it at any time.

The court says Uber’s user flow “fits many definitions of a ‘click-wrap agreement’, [but] might not be a ‘pure-form’ clickwrap agreement, because there is no ‘mechanism that forces the user to actually examine the terms before assenting.'” (“pure-form clickwrap”? UGH). It distinguishes the Berkson “Sign-in-wrap” (infinite number of ughs) case because ” Uber drew the drivers’ attention to the terms of the Service Agreement with bold, capitalized statements, and twice required the drivers to click “YES, I AGREE,” a much more explicit form of assent than the single clicking of a “SIGN IN” button.” Please note: if you ever use the term “sign-in-wrap” in a non-mocking way, another puppy will have a bad day (In other words, DON’T DO IT).

A quirk in this case: the plaintiffs are all Chinese, and they became drivers using a Chinese language version of the Uber app that nevertheless presented the contracts in the English language. The court expresses some skepticism about why Uber made foreign language versions of its app without translating the terms. Nevertheless, the court invokes the venerable contract doctrine: “failure to read a contract is not a defense to contract formation.” Citing the Mohamed case, the court brushes aside the unconscionability defense.

Singh v. Uber Technologies Inc., 2017 WL 396545 (D.N.J. Jan. 30, 2017). Another driver case that Uber wants to arbitrate. The formation analysis looks pretty similar to the Peng discussion. The court discusses that the contract has both mandatory arbitration and an exclusive venue clauses. Because the arbitration clause excludes IP and some other specified claims, the court says the provisions aren’t internally inconsistent. The analysis of the unconscionability challenge looks similar to the discussion in Peng.

HIDDEN TRACKS #2 By Eric: Another contract formation case.

DeVries v. Experian Information Solutions, Inc., 2017 WL 733096 (N.D. Cal. Feb. 24, 2017).

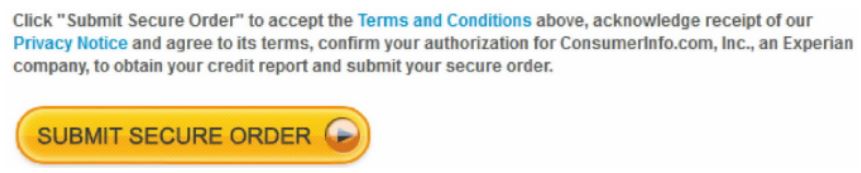

With regards to the above screen shot, the court upholds the contract formation:

DeVries argues that he did not consent to or have notice of the arbitration provision “by clicking on a button that did not mention, display, link to, or otherwise reference the Terms and Conditions.” This argument is unpersuasive. The text containing the Terms and Conditions hyperlink was located directly above that button and indicated that clicking “Submit Secure Purchase” constituted acceptance of those terms.

Experian changed the agreement since the plaintiff signed up. The court says “In general, courts have enforced new terms where prior agreements included change-in-terms provisions….Courts have also consistently applied arbitration agreements retroactively where the agreements explicitly subsume prior agreements or facially apply to disputes arising prior to the agreement.”

Related posts:

Anarchy Has Ensued In Courts’ Handling of Online Contract Formation (Round Up Post)

Courts Approve Terms of Service-Based Arbitration Clauses for Uber and Groupon

“Modified Clickwrap” Upheld In Court–Moule v. UPS

Evidentiary Failings Undermine Arbitration Clauses in Online Terms

Court Enforces Arbitration Clause in Amazon’s Terms of Service–Fagerstrom v. Amazon

‘Flash Sale’ Website Defeats Class Action Claim With Mandatory Arbitration Clause–Starke v. Gilt

Some Thoughts On General Mills’ Move To Mandate Arbitration And Waive Class Actions

Qwest Gets Mixed Rulings on Contract Arbitration Issue—Grosvenor v. Qwest & Vernon v. Qwest

Zynga Wins Arbitration Ruling on “Special Offer” Class Claims Based on Concepcion — Swift v. Zynga

“Modified Clickwrap” Upheld In Court–Moule v. UPS

Defective Call-to-Action Dooms Online Contract Formation–Sgouros v. TransUnion

Court Rejects “Browsewrap.” Is That Surprising?–Long v. ProFlowers

Telephony Provider Didn’t Properly Form a “Telephone-Wrap” Contract–James v. Global Tel*Link

2H 2015 Quick Links, Part 7 (Marketing, Advertising, E-Commerce)

Second Circuit Enforces Terms Hyperlinked In Confirmation Email–Starkey v. G Adventures

If You’re Going To Incorporate Online T&Cs Into a Printed Contract, Do It Right–Holdbrook v. PCS

Clickthrough Agreement Upheld–Whitt v. Prosper

The “Browsewrap”/”Clickwrap” Distinction Is Falling Apart

Safeway Can’t Unilaterally Modify Online Terms Without Notice